Unearthing green energy: The promises and perils of seabed minerals

Millions of years’ worth of decaying bacteria, plants, and animals fuel the world today. Fossil fuels—oil, coal, and gas—represent more than 80% of global energy production. They also account for over 75% of global greenhouse emissions and nearly 90% of carbon dioxide emissions.1

As nations seek to decarbonize their economies, they increasingly turn to renewable energy sources, including wind, solar, hydro, and bioenergy. In the coming decades, we may expect to see more solar panels covering rooftops, more wind turbines lining the landscape, and more electric vehicles driving down roads.

The International Energy Agency (IEA)’s Renewables 2024 report estimates the world will add more than 5,500 gigawatts of new renewable energy capacity between 2024 and 2030, almost three times the increase between 2017 and 2023.2 For context, 1 gigawatt could power more than 100 million LED lightbulbs or 750,000 homes.3

Recreational divers explore Silfra, a freshwater-filled rift in Iceland where the North American and Eurasian plates separate.

To build the batteries, magnets, motors, and electric networks needed to support these renewable energy technologies, though, the world is going to need a lot more minerals—materials like lithium, copper, cobalt, nickel, and zinc.

Proponents of renewable energy say the world has enough minerals to make the global energy transition to net zero, and measures could be put in place to recycle those minerals and to otherwise reduce the need for mineral mining long-term.

“But,” as Adair Turner, chair of the Energy Transitions Commission, has noted, “in some key minerals—particularly lithium and copper—it will be challenging to scale up supply fast enough over the next decade to keep pace with rapidly rising demand.”4

Demand for minerals is estimated to more than double by 2040, according to the IEA.5

Where will those minerals come from? Traditionally, mining operations have taken place on land. Now, there is growing interest in harvesting them from the deep sea.

Why look to the sea for minerals?

Mining on land is controversial. There are many concerns about environmental degradation and human rights violations, especially when mining is done in developing nations with minimal regulations.

Excavating minerals from the sea floor is no less controversial, and world leaders have approached the idea with hesitancy because of the complex, relatively uncharted—and important—oceanic ecosystem. While scientists have known about seabed minerals since the 1860s,6 commercial deep-sea mining is not currently underway.

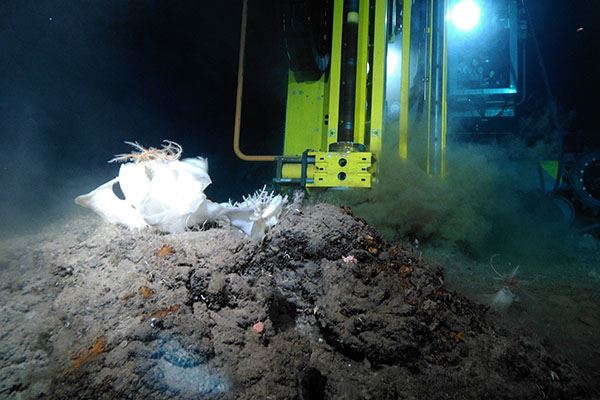

The FlexiCore™ marine coring system, shown during the Deep Insight 2023 expedition, enables efficient collection and analysis of seabed samples.

Still, the sea is an appealing place to look for the minerals needed for green energy. Decades of geological studies show there are untouched treasure troves on the sea floor, and expanding access to minerals would strengthen the security of the mineral supply chain.

Most mining done today is highly concentrated in a small number of countries. In many cases, one country controls the production and/or processing of a significant amount of a particular mineral. The Democratic Republic of Congo, for instance, supplies 70% of the world’s cobalt,7 and China refines about 35% of nickel, 50-70% of lithium and cobalt, and nearly 90% of rare earth elements.8

Having secure access to minerals is important to countries making the switch from fossil fuels to clean energy, especially to a country like Norway, which is already a heavy user of renewable energy.

The Scandinavian Peninsula nation generated 98% of its electricity from renewable sources in 20209 and is the fastest adopter of electric vehicles in the world, with an 80% share of vehicle sales being electric in 2022.10

Norway is considered a leading consumer of renewable energy, with nearly all of its electricity generation coming from renewable sources.

Norway manages marine areas five times larger than its land mass and earns 70% of its export earnings from ocean industries,11 so the idea that it could source its own minerals from the sea seems natural. But big questions remain: Can it be done in environmentally safe ways? And would it be economically worthwhile?

Project EMINENT

While the ocean poses unique technological and environmental hurdles, the demand for green-energy minerals makes it worth exploring to Norway. The country is one of the first to take serious steps toward deep-sea mining.

As of December 2024, Norway has paused its initial plans to begin awarding commercial exploration licenses in 2025. However, research is underway to gain a better understanding of the areas and ecosystems where seabed minerals may one day be harvested.12

One project, Project EMINENT, which stands for 'Energy MINerals for the NEtzero Transition,' is a research initiative bringing together 15 industry and academic partners to establish best practices for building a value chain for seabed minerals.

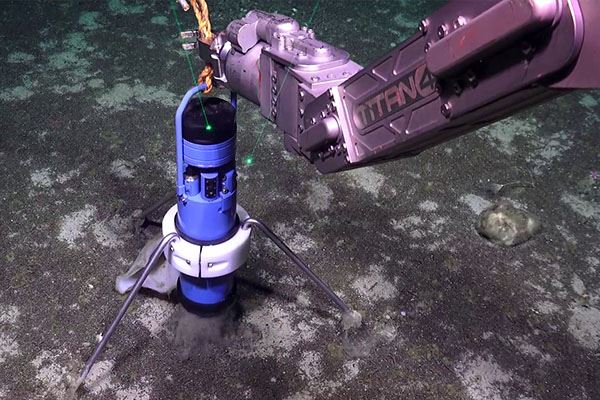

Environmental monitoring is critical to Project EMINENT. The Aanderaa SeaGuardII instrument—shown here during recovery with a Remotely Operated Vehicle (ROV)—collects seafloor data to establish baselines and ensure responsible practices in future mineral extraction.

With a budget of 139 million Norwegian kroner (~$12.5M USD), including about 71 million granted by the Research Council of Norway and Siva through the Green Platform initiative,13 Project EMINENT is laying the groundwork for what could be a game-changing shift in how we source minerals.

There are four main parts to the project: environmental, exploration, production, and processing, with environmental being the cornerstone, says Solveig Osjord, an exploration geologist who works for Adepth Minerals, the lead company on Project EMINENT.

Deep-sea mining critics have voiced fears that potential harm to marine biodiversity could accelerate climate change, which would be counterproductive in the pursuit of low-carbon energies. However, Project EMINENT partners believe seabed mineral mining could be less damaging than mining on land.

They are aiming for an 80% reduction in environmental footprint. Osjord says this should be possible, in part, through advanced technology and the concentrated nature of seabed minerals.

“We know some of these seabed mineral deposits may contain 5-10 times higher concentrations of these minerals compared to the land today,” Osjord says. “And the copper concentration, for instance, is way higher, so you can impact a smaller area and get more out.”

Knowing where to look for seabed minerals is also important.

The Mid-Atlantic Ridge

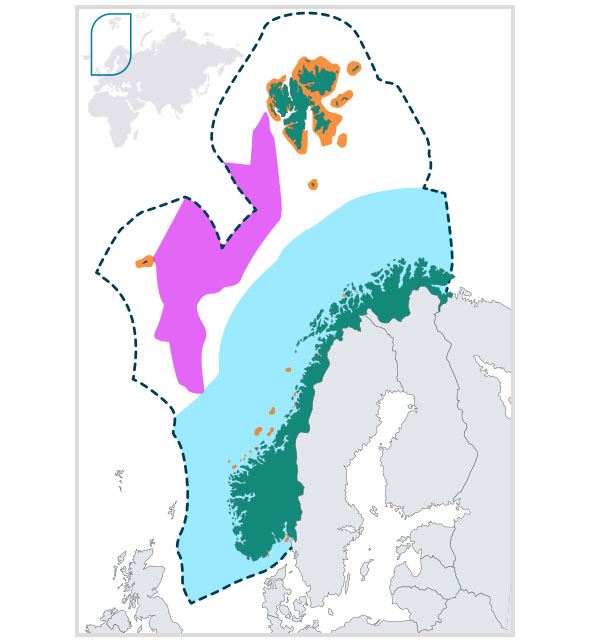

Norway is considering opening up to 280,000 square kilometers (108,000 square miles) of its ocean waters to seabed mineral exploration and mining.12 However, Osjord says actual mining activities will likely take place in areas about the size of a soccer field—and only where healthy mineral deposits are found and environmental studies show minimal impact.

Project partners are keying in on areas tens of kilometers away from active spreading at the Arctic Mid-Ocean Ridges, the northernmost portion of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, a massive underwater mountain range where the North American and Eurasian Plates are moving away from each other.14

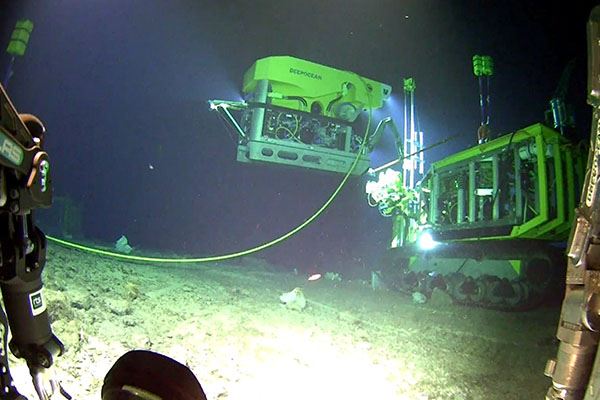

The Deep Insight expedition demonstrates simultaneous environmental, geophysical, and geological data acquisition.

As the sea floor spreads, it creates hot spots of circulating fluid—up to 400 oC (752 oF) pockets where conditions are ripe for both the formation of minerals and unique life. As rocks move further away from the active spreading site, they lose contact with the hydrothermal fluid and cool down to around 0 oC. These conditions are less conducive to biological activity, but the mineral deposits remain.

“We are not looking at the active systems,” Osjord says. “Because of the high temperatures of these active systems, you have a lot of microbial life and faunal species living off the heat and everything that is produced by the heat. It’s very important for us to avoid these special microbial communities, so we’re only looking at distant deposits.”

The current data and analysis, she adds, indicate that mining areas several kilometers away from the active spreading would affect fewer species than mining on land.

“However, it’s very important that we make a baseline and look at how we can manage our impact properly,” Osjord says.

Sensing the sea floor

To help build those baselines and to gain a clearer picture of the sea floor environment and how to protect it during mining operations, a portion of the Project EMINENT team set out to sea for the nearly-month-long Expedition Deep Insight in May 2023. The cruise, led by the University of Bergen, sailed two to three days from Port Haugesund through choppy waters to various study sites.

The team deployed ROVs, including one equipped with an Aanderaa SeaGuardII logger with cable-connected sensors to measure speed, tilt, heading, acoustic backscatter, pressure, salinity, temperature, oxygen, and turbidity as the ROV made transects just above the bottom of the sea. The ROVs took millions of photographs of the sea floor, which were then run through an AI program to detect what types of animals, rocks, geological structures, sediment types, and environmental conditions were present. Instruments were also left on the sea floor to collect data over time.

In addition, sensors helped monitor conditions while the team completed activities, such as testing a novel coring and drilling device, FlexiCore, adapted for deep waters. Instruments were deployed close to the operations and further away to help see how much impact a coring operation may have, down to seismic vibration levels. In parallel, coring devices collected rock, sediment, and water samples to test for eDNA, essentially looking for fingerprints that would tell the team which plant and animal species live in these areas, clues into how much they would be affected by mining.

The SeaGuardII deployed on the sea floor.

“The Aanderaa instruments give us a lot of insights into the bottom conditions of a specific area,” Osjord says. “This, together with eDNA results from sediment samples and water samples in addition to studies done on video footage from the area, will give us a good baseline of the biological conditions in an area.”

Dr. Anders Tengberg, product manager and scientific advisor for Aanderaa Data Instruments, says data collected by the Aanderaa instruments build on more than three decades of university research into minerals at the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. For the first time, though, the Aanderaa sensors enabled the measurement of currents and other parameters just above the sea floor.

“Before, they were measuring further up,” Tengberg says.

He adds that the measurements help detect resuspension events, which indicate movement. They are also used to calibrate and validate circulation and water quality models, which are important for understanding and forecasting these areas.

Expedition Deep Insight team members pose on deck during their May 2023 research voyage to collect critical seafloor data.

“You get such detailed information about what’s happening,” Tengberg says. “You can see the currents, but we also have sensors which feel if the sea floor moves some millimeters over time periods of months to years or if you have a rotation of the ground. The magnetic north is all the time changing, so you can see that. You can also detect the movements of swimming animals as well as changes in particles, temperature, oxygen, and salinity, which are related to seasonal changes and/or seismic activities. You get the advantages when you put something directly at the bottom that measures many parameters in very high detail.”

Map showing Norway (green), Norwegian economic exclusive zone (light blue), proposed area for deep sea mining (pink), and marine protected areas (orange). The dashed line represents the outer limit of the continental shelf.

Just a start

As of late 2024, the Aanderaa tools have collected about 10 months of data for Project EMINENT. Tengberg says he would like to see a minimum of two-to-three years of data so that occasional but impactful events can more likely be detected. Preliminarily, he says it looks like seabed mining, based on the data he has seen, would not create major environmental issues in terms of the spreading of suspended sediments.

Aanderaa SeaGuardII instruments will continue collecting environmental data to assess seabed mining viability and impacts. Photocredit: Anders Tengberg

Osjord adds that all data and analysis done thus far, together with technological advancements within the field, suggests seabed mineral extraction can be environmentally and economically viable. However, there are still many questions to answer and more data to evaluate. The team has found high concentrations of copper, but the entire endeavor in remote waters would be quite expensive. Project EMINENT is expected to continue through at least 2025, and environmental studies will continue beyond this project.

“The nice thing about this project is we have experts in every single one of these groups, so getting together, discussing, giving each other input, it gives a lot of valuable insight into what we have to look into and how to do it,” Osjord says. “We have kind of a broad picture, and we need more pieces to it. It’s very exciting.”

As Project EMINENT progresses, one thing is clear: The road to net-zero energy is paved with questions that demand answers. Stay tuned as science and industry explore what lies beneath.

Additional Information

The Status of deep-sea mining

Deep-sea mining is the excavation of minerals from the sea floor. Seabed minerals are desirable for producing metals needed to build renewable energy technologies, such as batteries, solar panels, and wind turbines.

Solveig Osjord, exploratory geologist with Adepth Minerals, says seabed minerals are found in:

- Polymetallic nodules, which are potato-sized chunks of rock typically rich in cobalt, copper, nickel, and rare earth minerals.

- Ferromanganese crusts, which have a similar composition to nodules but grow on sea mounts as crusts.

- Polymetallic sulfides, which are typically rich in copper, zinc, and could be rich in gold, silver, and, to some extent, rare earth elements. These are associated with spreading ridges and are the focus of Project EMINENT.

Some exploratory mining has occurred at a small scale, but deep-sea mining is not currently operational commercially. This may change in the next few years, though.15

The United Nations’ International Seabed Authority (ISA), formed in 1994, has until 2025 to finalize regulations related to seabed mining in international waters due to a process kicked off in 2021 when the Pacific Island nation of Nauru announced its intention to begin mining in international waters.15 The ISA controls mineral-resources-related activities in about 54% of the total area of the world’s oceans.16

Sources:

- United Nations, Renewable energy – powering a safer future

- International Energy Agency, Massive global growth of renewables to 2030 is set to match entire power capacity of major economies today, moving world closer to tripling goal

- CNET, Gigawatt: The Solar Energy Term You Should Know About

- Energy Transitions Commission, New Report: Scale-up of critical materials and resources required for energy transition

- International Energy Agency, Outlook for key minerals

- UN Chronicle, The International Seabed Authority and Deep Seabed Mining

- International Energy Agency, Clean energy supply chains vulnerabilities

- International Energy Agency, The Role of Critical Minerals in Clean Energy Transitions

- International Energy Agency, Norway 2022

- World Resources Institute, These Countries Are Adopting Electric Vehicles the Fastest

- Norwegian Government Security and Service Organisation, The ocean nation of Norway

- BBC, Norway suspends controversial deep-sea mining plan

- GCE Ocean Technology, EMINENT – Energy MINerals for the NEtzero Transition

- The Geological Society, Mid-Atlantic Ridge

- World Resources Institute, What We Know About Deep-Sea Mining – And What We Don’t

- International Seabed Authority, About ISA