The Clean Water Act - How a Small Fire Sparked Big Changes

Throughout 2022, YSI will be celebrating the Clean Water Act's 50th anniversary by bringing awareness to what the law has accomplished and to some of the great things water quality advocates have done.

In this blog, you'll learn about details of the law and its impact, including:

- Events leading up to the passage of the Clean Water Act.

- Political drama – bipartisanship and a presidential veto!

- What the law actually does and how it has changed.

- What the CWA means for our customers.

- Controversies!

- How you can support water quality!

The Cuyahoga River in Ohio, United States, burned at least a dozen times between 1868 and 1969 due to pollution in the water. While an infamous fire in 1969 caught the country's attention, there are no known photos of the fire because it was extinguished so quickly. The image here is from a fire in 1952. (Michael Schwartz Library at Cleveland State University)

The August 1, 1969 issue of TIME Magazine revealed to the rest of the U.S. what residents of Cleveland, Ohio, already knew – the Cuyahoga River was prone to catching fire. The river had burned at least a dozen times between 1868 and 1969. While the fire in 1969 was short – it was extinguished in 24 minutes1 – it proved to be the most impactful.

Leading up to the infamous fire in '69, the river was devoid of life and was an oily mess that bubbled with subsurface gases. It seemingly "oozed" rather than flowed.2 Decades of industrial pollution had essentially turned the river into an open sewer.

Shown here in 1964, the Cuyahoga River in Ohio, United States, became an oily, lifeless open sewer after decades of pollution from industrial sources. (Michael Schwartz Library at Cleveland State University)

While Clevelanders were becoming increasingly motivated to clean up the Cuyahoga – they approved a $100 million cleanup program in 19683 – the shock and outrage of the wider American audience in response to the TIME article turned this small fire into a watershed moment for U.S. water quality.

Appetite for Environmental Action

The catalyst of the modern environmental movement is often cited as the release of Silent Spring in 1962. Authored by Rachel Carson, it illuminated the negative impacts of DDT, a commonly used insecticide. Other events in the 1960s – such as the Santa Barbara oil spill in January 1969 – further fueled the public's desire for environmental protection.4 When the Cuyahoga caught fire (again) in 1969, it was clear that something needed to be done – the public outcry was loud and clear.

Events such as the release of Rachel Carson's Silent Spring in 1962, the Santa Barbara oil spill in January 1969, and the Cuyahoga River fire of 1969 inspired the first Earth Day in 1970. Shown here is the front page of The New York Times on April 21, 1970.

1970 was an important year for the modern environmental movement. An estimated 20 million people participated in the first Earth Day, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) was established, and the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) was created to monitor and improve the conditions of the oceans.4

But a major piece of legislation was on the horizon that would fundamentally change the protection of our waterways.

Passage of the Clean Water Act

On October 28, 1971, Edmund Muskie (D-ME) introduced S. 2770, a bill to amend the Federal Water Pollution Control Act.5 This older piece of legislation was passed in 1948, and it had proven to be ineffective – it was not preventing pollution from pouring into U.S. waterways.

With an objective to "restore and maintain the natural chemical, physical, and biological integrity of the Nation's waters," S. 2770 would ultimately become known as the Clean Water Act (CWA).6

Bipartisan Support in Congress

The Senate passed Muskie's bill in November 1971, while the House passed it in March 1972. There were drastic differences between the versions passed by each body of Congress. Luckily for all of us, these differences were ultimately worked out, and the final version of the Federal Water Pollution Act of 1972 passed with strong bipartisan support – 366 to 11 in the House and 74 to 0 in the Senate.7

What a rare accomplishment – overwhelming support for an environmental law!

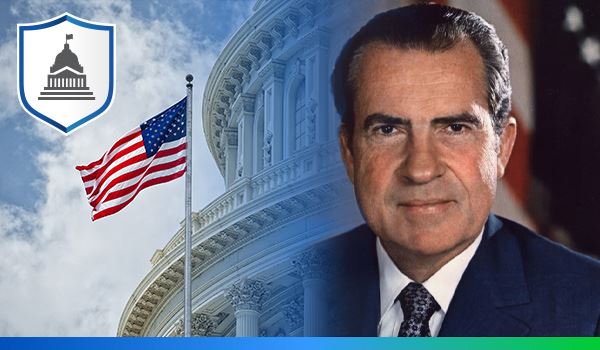

While Congressional and public support for the legislation was strong, it still had to be signed into law by President Richard Nixon.

Nixon Vetoes

While the Nixon Administration was not wholly opposed to protecting water quality, it was opposed to the price tag of the final bill – an estimated $24.6 billion. Despite Nixon's own EPA administrator supporting the legislation, the President vetoed it on October 17, 1972.8

President Richard Nixon's administration was not opposed to environmental legislation, as was demonstrated by the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency in 1970 and the enactment of the Clean Air Act of 1970. However, Nixon was opposed to the expected cost of the Clean Water Act. While he vetoed the bill, Congress voted to override his veto.

As you may remember from grade school, Congress can vote to override a veto, but it's hard to do – it requires a two-thirds vote in both the House and the Senate. In the history of the U.S., less than 10% of presidential vetoes have been overridden!9

Despite this poor track record, the Senate and the House voted to override Nixon's veto on October 18, 1972.7 You can check out the final version of the bill on the U.S. Government Publishing Office's website.

What Does the Clean Water Act Do?

In general, the Clean Water Act (CWA) established a structure for protecting water quality that was to be implemented by the EPA in partnership with each state in the United States.10 There are several areas where the CWA has resulted in significant improvements to water quality:

- National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES): a permit system that enforces point source discharge requirements. Anyone discharging pollutants into a U.S. waterway via a point source must obtain one of these permits.

- Water Quality Standards (WQS): states must identify water bodies with water quality that isn't suitable for their intended use. A Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) of the pollutant(s) causing the impairment must be established for these waters, and a plan put in place to improve water quality.

- Regulate Discharge of Dredge or Fill: a permit is required before dredged or fill material from certain activities (e.g., land development) can be discharged into waters of the United States.11

National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES)

As the Cuyahoga River demonstrated, the unregulated release of contaminants into a water body can turn it into a toxic soup. The CWA addressed this by regulating the discharge of pollutants from a "point source" into "waters of the United States" .5

The terms "point source" and "waters of the United States" are broad,12 but a classic example is a pipe from a wastewater treatment plant that discharges into a river.

An integral part of the Clean Water Act is the NPDES permitting system that regulates the discharge of pollutants from a point source, such as a pipe.

Managing waste discharge from point sources is primarily accomplished through the EPA's National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES). Any point source discharge of pollutants into U.S. waters must be regulated by an NPDES permit.5 Today, most states are authorized by the EPA to manage NPDES permits.10

A permit contains details such as the acceptable level of a pollutant. Sometimes, it's up to the permittee to select an appropriate technology to achieve the pollutant level. Other times, the permit will provide generic best management practices (BMPs) that limit pollutant levels, such as a screen installed over a pipe.12

Even if you do not need an NPDES permit, it's important to realize the facility treating your waste does. Please be careful what you pour down the drain, as hazardous chemicals may not be adequately treated and ultimately end up in surface waters. They can even diminish the overall effectiveness of the treatment process.13

The regulation of point sources is one of the most critically important roles of the CWA. Another is the development of water quality standards.

Water Quality Standards (WQS)

The CWA requires each state to establish Water Quality Standards (WQS) for each water body within its boundary. States must identify the use of a water body, such as drinking water supply, swimming, or agricultural use.10

Criteria must be developed to support its use, such as the maximum allowable amount of a specific chemical that can safely be present in a drinking water reservoir. If you're an angler, these criteria can help ensure that the fish you're trying to catch live in a healthy habitat with enough dissolved oxygen present.10

States regularly monitor their waters and determine those that don't meet their WQS. An impaired waters list must be updated and resubmitted to the EPA every two years. A Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) – the maximum amount of a pollutant that can be present and still meet WQS – is established for the impaired waters.14

Once a TMDL is established, any necessary change(s) to point-source pollutant loading in the water body is implemented through NPDES permitting (i.e., TMDLs are integrated into NPDES permits issued in the area). Nonpoint sources of pollution are addressed in various ways15 – see the section on the Water Quality Act of 1987 for more information on nonpoint sources and the CWA.

The largest and most complex TMDL is for the Chesapeake Bay in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States.

More than 40,000 TMDLs have been completed since the passage of the CWA. The largest and most complex TMDL is in the Chesapeake Bay, and it is currently estimated that all pollution control measures will be fully in place by the end of 2025. You can read more about the Chesapeake Bay TMDL on the EPA's website.

Regulate Discharge of Dredge or Fill

Aquatic environments like wetlands, streams, and rivers can be drastically altered if dredge or fill materials are deposited into them. The CWA addressed this in Section 404.

Unlike other areas of the CWA that are overseen by the EPA, permits for the discharge of dredged or fill material into waters of the U.S. are managed – at least on a day-to-day basis – by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE). The EPA still does play a role, as it can veto any permits if the project would cause unacceptable degradation of water quality.10

Under the Clean Water Act, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers is tasked with issuing permits for the discharge of dredged or fill material into waters of the United States.

Examples of activities that must receive a permit from USACE include infrastructure development and mining. However, before these are approved, two criteria must be satisfied:11

- There is not a reasonable alternative available that is less damaging to the waters of the U.S.

- Waters of the U.S. must not be significantly degraded.

Some important exemptions to the dredge and fill discharge portions of the CWA were made in the Clean Water Act of 1977, a bill that amended the CWA.

There are several other ways the CWA protects water quality, but some of them have been modified – or even added – with subsequent legislation.

Clean Water Act Amendments

Portions of the CWA have been amended since it was passed in 1972. The two most substantial amendments were part of the Clean Water Act of 1977 and the Water Quality Act of 1987.

Clean Water Act of 1977

Concerns were raised after the passage of the CWA that Section 404 – the portion that covers dredge and fill – would negatively impact agriculture. The Clean Water Act of 1977 resulted in some exemptions to Section 404, including normal farming, ranching, and forestry activities.16

These amendments specify that only "normal farming" activities would be exempted, such as plowing, cultivating, minor drainage, and harvesting. Activities must also be associated with an ongoing operation. For more details on Section 404 exemptions, check out the EPA's memorandum on Clean Water Act Section 404 Regulatory Program and Agricultural Activities.

Amendments to the Clean Water Act passed in 1977 exempted "normal farming" activities – such as minor drainage – from complying with the requirements of the law.

The 1977 amendments also required large municipalities – specifically their wastewater treatment facility – to create a pretreatment program to treat or remove wastes before being discharged. Also included were those that received considerable waste from industry.10

Water Quality Act of 1987

While the CWA addressed point source pollution, it did very little to address nonpoint source pollution (e.g., stormwater runoff). This was particularly problematic, as it was estimated that over 50% of the United States' remaining water pollution issues were tied to nonpoint sources.17 The Water Quality Act of 1987 changed this.

The bill included the Section 319 Grant Program that provides states funding to implement various activities and projects addressing nonpoint source pollution. States receive the funding and often sub-grant the money to local organizations that implement projects designed to eliminate known impairments, restore impaired waters, and reduce nonpoint source pollutants.18

The Water Quality Act of 1987 specified that stormwater was subject to NPDES permitting, specifically municipal separate storm sewer systems (MS4s) and industrial stormwater dischargers.17 This was a big breakthrough, as polluted stormwater runoff often travels through MS4s and is not always treated before being discharged into a water body. Read more about Stormwater Discharges from Municipal Sources on the EPA's website.

The Water Quality Act of 1987 addressed stormwater by requiring municipal separate storm sewer systems (MS4s) and industrial stormwater dischargers to obtain an NPDES permit. Shown here is a storm drain outflow.

There were other updates to the CWA in the bill. The CWA originally included a Construction Grants program that supported the development of municipal wastewater treatment facilities. The Water Quality Act of 1987 replaced this program with a State Revolving Fund (SRF) program still in existence today.10 This program has been a tremendous help to many municipalities.

Practical Implications for Wastewater Monitoring

Wastewater treatment plants – sometimes called water resource recovery facilities (WWRFs) – discharge treated effluent into receiving waters such as streams, rivers, and lakes. This is an excellent example of a point source, so these facilities have an NPDES permit they must comply with. If they release contamination at levels that exceed their permit, the municipality is subject to heavy fines.

Municipalities have no interest in exceeding limits on their permits, so wastewater managers rely on instrumentation to keep a close eye on their facilities.

Rather than exclusively analyzing samples at a few points in the treatment process (e.g., from the effluent), many managers monitor water quality parameters throughout the treatment process to ensure they are within acceptable limits. This prevents any surprisingly high pollutant concentrations in the effluent. YSI's IQ SensorNet network of online controllers and sensors is an ideal monitoring solution for WRRFs.

Many wastewater treatment facilities find it beneficial to monitor water quality parameters throughout the treatment process. This helps ensure their effluent will comply with their NPDES permit.

NPDES permits can be impacted by updated discharge requirements – including those resulting from new TMDLs – and WRRFs must respond to these changes.

A great example of a WRRF responding to new discharge requirements can be read about in our application note on Wastewater Nutrient Removal and Preservation of Chesapeake Bay. In this story, the Washington Suburban Sanitary Commission (WSSC) was assessed new discharge requirements for allowable nitrate in treated effluent to achieve nitrogen loading reduction commitments set forth in the Chesapeake Bay Program.

For the WSSC Seneca facility, a new denitrification process was required as part of an upgrade to achieve enhanced nutrient removal (ENR). The primary goal for the denitrification process was to implement a solution that reduced total nitrogen (TN) in treated effluent to less than 4.0 mg N/L, and to minimize operating costs as much as possible.

In order for operations to meet the stringent treatment requirements, the Seneca team needed monitoring technology that could provide accurate, real-time data to continuously keep an eye on the process. Ultimately, the team chose YSI NitraVis® UV-Vis nitrate sensors due to performance features such as UltraClean™ technology that prevents biofouling and lowers maintenance requirements. The modular design of the YSI IQSN system was also a big factor.

In summary, the Clean Water Act resulted in significant changes for wastewater treatment, but it isn't the only water quality application where it's had an impact.

Practical Implications for Surface Water Monitoring

Surface water monitoring is an integral part of fulfilling the purpose of the Clean Water Act. As was discussed in the section on Water Quality Standards (WQS), states are required by the CWA to regularly monitor their waters and determine those that don't meet their WQS. For waters that are impaired, water quality monitoring helps in the development of TMDLs.

Water monitoring under the CWA is not a one-time thing. For example, an impaired waters list must be updated and resubmitted to the EPA every two years. Frequent monitoring is also how the success of a TMDL is determined.

It is preferred to collect measurements in situ. Collecting samples and analyzing them later in a lab can cause issues related to biodegradation, growth, settling, precipitation of minerals, and more, although there are methods to help preserve samples.

Water quality monitoring in surface water is often completed with a long-term monitoring device, such as the YSI EXO sonde shown here.

Submersible sensors are portable and can be placed directly in the water (e.g., a stream). Instruments like the YSI ProDSS are designed for spot sampling, while the YSI EXO is intended for continuous, unattended monitoring. Continuous monitoring provides a more comprehensive view of the state of water quality in a waterbody than traditional grab sampling methods, offering a more reliable understanding of water quality.

Check out our application note on State Promulgates TMDL's Based On Sporadic Grab Sampling to learn how continuous water quality monitoring stations provided a more accurate representation of the Gills Creek Watershed (South Carolina) than grab samples.

Practical Implications for Laboratory Analysis

While in situ data collection is often preferred, some NPDES permits or TMDLs require laboratory analysis of a sample.

The EPA is tasked with releasing laboratory methods for the analysis of samples. These procedures are used by industries and municipalities when analyzing the collected sample's chemical, physical, and biological components.19

There are a variety of lab instruments from YSI, OI Analytical, and other Xylem brands that utilize EPA methods. One example is the OI Analytical 4760 Eclipse Purge and Trap used in conjunction with the 4100 Sample Processor. This setup can follow EPA Method 624.1 to determine purgeable organic pollutants in various discharges and environmental samples, as is discussed in our blog post on Purgeable Organic Compounds in Wastewater by Purge and Trap with Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry.

The OI Analytical 4100 Sample Processor and 4760 Eclipse Purge and Trap can be used to follow EPA Method 624.1 to determine purgeable organic pollutants in various samples.

Suppose you're analyzing samples in a laboratory, and you have to follow an EPA test method. In that case, we recommend you check out the EPA's page on Clean Water Act Analytical Methods for the latest information on accepted methods.

Has the Clean Water Act Been a Success?

No longer an open sewer that collects a vast amount of industrial waste, the Cuyahoga River has reaped the benefits of the bill it inspired.

Since the passage of the Clean Water Act in 1972, the Cuyahoga River has steadily improved. Now designated as an American Heritage River, a portion of it even runs through the only national park in Ohio – Cuyahoga Valley National Park. Not only is it safe for recreation, but fish from the river are also safe to eat.20 What a turnaround for a river that was lifeless 50 years ago!

The Cuyahoga River – seen here with Cleveland, Ohio's skyline in the background – is a shining example of how the Clean Water Act has dramatically improved water quality in the United States.

The benefits of the CWA reach far beyond the Cuyahoga River. According to American Rivers, the legislation has prevented billions of pounds of pollution from ending up in our rivers. Since the bill's passage, the number of waters that meet clean water goals has doubled.

Others have also proven the positive impact of the CWA. Researchers at UC Berkley analyzed data from 240,000 monitoring sites between 1962 and 2001. Nearly every pollution measure improved during this period, and the team also concluded that the number of rivers deemed safe for fishing increased by 12%.21

While the CWA has driven many positive impacts, it remains one of the most controversial pieces of legislation in the history of the United States.

Clean Water Act Controversies

Two specific aspects of the CWA that have been controversial include – 1) the cost vs. benefit of the law, and 2) the interpretation of "waters of the United States."

Several research teams – including those at UC Berkley mentioned in the section above – have concluded the costs associated with the CWA have outweighed the benefits. This contrasts with other major pieces of environmental legislation, like the Clean Air Act.21 These studies consider many variables, so it's important to remember that any assumptions used may not reflect reality.

As mentioned in the section on the National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System, "waters of the United States" – sometimes referred to as WOTUS – is a very broad description. WOTUS establishes the scope of federal jurisdiction under the CWA, so it's not surprising the interpretation of WOTUS has been the source of considerable controversy.

Environmental advocates want the definition of WOTUS to be broad, while others want it to be narrow, allowing states to manage their resources how they would like.22

The definition of "waters of the United States" continues to be contested, primarily because this definition establishes the scope of federal jurisdiction under the Clean Water Act.

Farmers, home builders, and others that work the land are particularly concerned with how WOTUS is defined. While these groups most certainly want clean water, a broad interpretation may mean puddles, drainage ditches, or small ponds on their property are subject to the CWA. Obtaining permits can require significant time and money, all while doing little – or nothing – to protect water quality.

There have been three U.S. Supreme Court decisions and a series of rules released by the EPA that have attempted to address the interpretation of WOTUS. For an overview of how the definition has changed over time and to see the most updated guidance on WOTUS, check out the EPA's webpage on About Waters of the United States. An overview video from 2019 that describes WOTUS can be seen here.

How to Support Water Quality

While the Clean Water Act has certainly improved water quality in the United States, there's still plenty of work to be done. There are several ways you can help restore and maintain our waters, including:

- Pick up trash! Trash will eventually find a water body, so it's best to pick it up if you see some on the ground. You can also retrieve it from water to prevent it from going further downstream. At YSI, we've participated in some events where we paddle down a river and pick up trash we find. We've also gone plogging!

- Enjoy our waterways! This will keep you motivated to protect our Nation's waters. You may even find a new hobby!

- Dispose of waste properly! Don't pour toxic household chemicals down the drain, and don't pour used oil or antifreeze into the storm drain or the street.23

- Provide feedback! Public hearings are required whenever water quality standards are revised, and the EPA must consider public comments they receive on proposed federal regulations.24

- Contact your local legislator! They can champion legislation that will make a difference in water quality in your community.

- Contribute to a nonprofit! Xylem partners such as EarthEcho are engaged in helping communities across the globe monitor their local bodies of water.

Sources:

- Outside, 51 Years Later, the Cuyahoga River Burns Again

- TIME, America's Sewage System and the Price of Optimism

- Smithsonian Magazine, The Cuyahoga River Caught Fire at Least a Dozen Times, but No One Cared Until 1969

- PBS, The Modern Environmental Movement

- EPA, Summary of the Clean Water Act

- US Capitol Visitor Center, S. 2770, Federal Water Pollution Control Act Amendments of 1972

- Waterkeeper Alliance, The Bipartisan Beginnings of the Clean Water Act

- New York Times, President Vetoes Clean Water Bill

- Center for Legislative Archives, The Presidential Veto and Congressional Veto Override Process

- EPA Alumni Association, Water Quality: A Half-Century of Progress

- EPA, Permit Program under CWA Section 404

- EPA, NPDES Permit Basics

- EPA, What Can You Do to Protect Local Waterways?

- EPA, Overview of Identifying and Restoring Impaired Waters under Section 303(d) of the CWA

- EPA, Overview of Total Maximum Daily Loads (TMDLs)

- EPA, Memorandum: Clean Water Act Section 404 Regulatory Program and Agricultural Activities

- City of Cape Girardeau, History of Federal Clean Water Regulations

- Ohio EPA, Clean Water Act, Section 319 Grant Program

- EPA, Clean Water Act Analytical Methods

- Cincinnati.com, Fish in river that famously caught fire now OK'd for dinner

- UC Berkeley, Clean Water Act dramatically cut pollution in U.S. waterways

- Eos, New Clean Water Act Rule Leaves U.S. Waters Vulnerable

- Nature, How We Protect Watersheds

- EPA, Things You Can Do to Protect Water Quality