Guarding the Pa Sak River

(Updated November 2021)

Thailand, as with the majority of its fellow ASEAN countries, has experienced rapid population growth and industrial development over the past few decades, particularly in their large city centers (e.g., Bangkok).

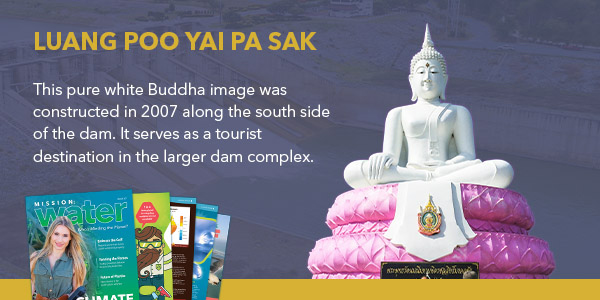

A Buddha statue at sunrise, overlooking the Pa Sak River and Cholasit Dam. Khao Phra Ya Dern Thong view point. Phatthana Nikhom, Lopburi

Along with the benefits of this economic growth, there are also associated costs, which often surface as unexpected externalities, such as air and water pollution.

The Water Environment Partnership in Asia (WEPA) recently rated Thailand’s overall surface water quality fair and improving in the majority of its river basins.

However, rivers in the south, adjacent to the major city centers, remain stressed by municipal, agricultural and industrial pollution sources.

These continuous stressors ultimately result in deleterious local events such as harmful algal blooms (HABs), extreme hypoxic or even anoxic water formation, and extensive natural and aquaculture-grown fish kills.

Water Quality Monitoring Network – Installations such as these dot the Pak Sak river at regular intervals, keeping a close eye on changes that could impact the rest of the country.

One such river, the Pa Sak, located within the Chao Phraya River drainage basin, has been most affected by anthropogenic activities over the years, primarily from municipal and industrial wastewater discharge.

Several recent large and high-profile fish kill events (e.g., Trichopodus trichopterus - an abundant local gourami species) have prompted the government to take action, including funding real-time water quality monitoring stations.

The Pa Sak

Geographically, the Pa Sak River’s upper reaches originate in the steep mountain forests and streams of the Phetchabun Mountains of Northern Thailand.

Its waters eventually empty into the Lopburi River system near the ancient capital city of Ayutthaya (north of Bangkok), a United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) World Heritage Site, and then finally into the Chao Phraya basin. The large disparity in rainfall from wet and dry seasons often produces extremes in water level and flow.

With superimposed effects of climate change that are exacerbating drought and flooding events, farming — predominantly rice farming and aquaculture — are a more risky business for locals.

Photo: JOYFULLIFE / Shutterstock.com

The Pa Sak Cholasit Dam

The Pa Sak Cholasit Dam in Lopburi Province was commissioned in 1999 to help stabilize water supply and reduce the risk to farmers and water managers; it also produces ~6MW of electricity for the region.

It’s considered one of the largest irrigation projects in Thailand, and its inauguration was presided over by the late King Bhumibol Adulyadej.

The gate of Pa Sak Cholasit Dam. This was a major national project that now provides flood control for Bangkok and serves as a regional tourist destination.

According to the Pollution Control Department’s Booklet on Thailand State of Pollution 2018, the Pa Sak falls in the “fair water quality” bucket, with a water quality index (WQI) of 61 (good quality is a WQI of 70 and above).

Recent improvements in water treatment technology, construction of four new wastewater treatment plants, and active water quality monitoring are credited for an overall increase in the Pa Sak’s WQI.

Based on PCD’s 2015 report, only 45% of wastewater had been treated prior to release into its adjacent rivers, but there have been recent improvements in this percentage.

Government displays were installed at each site, which builds public awareness of the project and encourages participation in data viewing.

Pisces Buoys

The Pisces buoys were assembled by YSI’s Integrated Systems and Services in the U.S., and delivered to Green Banyan in two phases.

The first set of four Pisces buoys were delivered and installed in 2016, while the second set of four buoys were delivered and commissioned recently.

The eight buoys are serviced monthly, where the team travels to each site to check all systems, calibrate the sensors, and provide general maintenance and cleaning.

Government agencies and universities use the data in active monitoring, numerical and predictive model development, and public awareness programs.

Water quality data are transmitted to a government server and Green Banyan. An alarm system provides officials with real-time warnings if a parameter (e.g., dissolved oxygen) exceeds the government-recommended threshold.

Notifications are then transmitted to the local community for appropriate response.

Monitoring Stations. Sites like this come in a diversity of sizes and security along the Pa Sak in a large scale monitoring network.

Phase Three

The next phase of the Pa Sak River water quality monitoring project features an additional four monitoring stations installed along the Pa Sak.

The new installations are land-based, unlike the buoy platforms of the first two phases.

Making a Splash. Green Banyan and YSI staff on hand to celebrate the launch of the Pisces buoy-mounted monitoring system. Left-to-Right: Kittapol Nakchavee and Sukhon Duangcharoen from Green Banyan. Eric Law and Jason Hung from YSI Hong Kong.

These stations include both the original EXO parameters (e.g., pH, ammonia, etc.), as well as Biological Oxygen Demand (BOD) and Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD) by employing a WTW NiCaVis spectral sensor package.

These parameters are traditionally used in wastewater monitoring applications and thus can be used as means of comparing water quality from treatment plants to the river.

The Green Banyan team sends their first Pisces Buoy on its maiden voyage. The large crane-like structure (i.e., the cantilever) brings the Pisces in and out of the water. It also helps keep the Pisces on station during flooding events.

Overall, the aim of this program is not only to help enforce the local environmental laws but also to strengthen the relationship and confidence between citizens and industry, explains Green Banyan’s Opart Rungsiri.

It also allows researchers and agencies to provide an overall picture of the Pa Sak’s health and response to tighter pollution regulations, as well as serve as a “proof-of-concept” for similar future projects in the Chao Phraya basin and beyond.

Wat Phanan Choeng | Ayutthaya, Thailand Located where the Pa Sak River and Chaeo Phraya River meet.