Weathering the Storm: Dominica’s Leap in Flood Preparedness

Deep blue ocean waters. Lush tropical vegetation. Soaring cliffs. Glistening rivers. Majestic mountains.

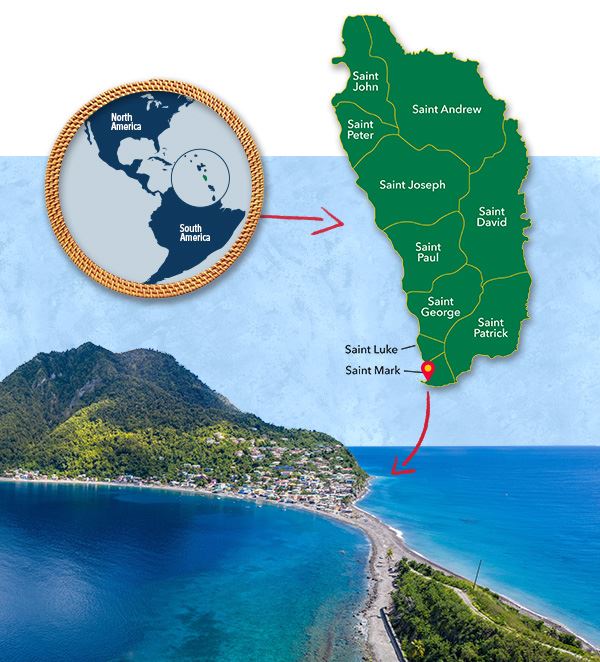

The island nation of Dominica, correctly pronounced daa-muh-NEE-kuh, features postcard-perfect scenery.

Nestled roughly halfway between Puerto Rico and Trinidad and Tobago in the Caribbean archipelago, Dominica boasts the highest mountains in the Lesser Antilles region. Active volcanic activity creates its Boiling Lake, hot springs, and fumaroles. The Atlantic Ocean lies to the east, and the Caribbean Sea to the west.

Dominica is part of a collection of islands in the Lesser Antilles region of the Caribbean Sea. Known as the

Dominica is part of a collection of islands in the Lesser Antilles region of the Caribbean Sea. Known as the

"Nature Island of the Caribbean," it is celebrated for its beautiful landscapes, flora, and fauna.1 The flag of Dominica features the national bird, the Sisserou parrot, and 10 stars representing each administrative division (i.e., parish).1

Its people claim Dominica has as many rivers as days in the year. While that may be an exaggeration, many streams and rivers cascade down towering mountain peaks. Farms and rainforests cover steep slopes, and most of the population of more than 74,000 lives in coastal communities.1

Scotts Head, a village located on the southwest coast of Dominica within the Saint Mark Parish.

Scotts Head, a village located on the southwest coast of Dominica within the Saint Mark Parish.

Despite the picturesque setting, the combination of its location, landscape, and dependence on agriculture and nature tourism have earned Dominica the distinction of the Caribbean island most vulnerable to natural disasters.

As weather systems move through the area, clouds form when they interact with the tall mountains that generally run north to south in the center of the island. They drop an abundance of rain. For example, one localized, unnamed event unleashed roughly 43 cm (17 in.) of rain in 24 hours on one side of the island.

As rainwater flows down the mountains to the sea, it swells rivers and washes away soil, causing flash floods and landslides that threaten the Dominican people and their livelihoods. Hurricanes, tropical storms, and other natural disasters decimate crops, fisheries, homes, and infrastructure.

Building Resiliency

In September 2017, Hurricane Maria rapidly escalated from a tropical storm to a Category 5 within 24 hours as it approached Dominica.2 Though the storm is best remembered for its catastrophic destruction in Puerto Rico, it caused similar or greater devastation in Dominica. Nearly every roof on the island was damaged, and its impact in damages and losses was $1.4 billion, or 226% of Dominica’s 2016 gross domestic product.3

Days later, Prime Minister Roosevelt Skerrit declared to the UN General Assembly that The Commonwealth of Dominica aspired to become the world’s first climate-resilient nation.2

Those efforts were already underway, thanks to a World Bank grant and highly concessional financing the country applied for in 2012. Dominica received grant approval and developmental financing below market rate in 2014 under the Pilot Program for Climate Resilience. Collin Guiste, project coordinator for the Dominica Disaster Vulnerability Reduction Project, leads the effort.

To reduce Dominica’s vulnerability to natural disasters, a network of monitoring stations with hydrometeorological sensors was recently installed across the island. Each station features a rain gauge that monitors rain rate and total rainfall.

To reduce Dominica’s vulnerability to natural disasters, a network of monitoring stations with hydrometeorological sensors was recently installed across the island. Each station features a rain gauge that monitors rain rate and total rainfall.

“The comprehensive effort to develop and build systems and infrastructure to reduce vulnerability to natural disasters and climate change started in 2014,” he says.

Hurricane Maria exposed the depth of the island’s vulnerability. Following that storm, Guiste says the project addressed many fragile systems. For example, eight new water storage tanks and improvements to associated access roads, as well as supply and distribution lines, ensure access to clean water. Pre-engineering and design will support the rehabilitation and improvement of 30 km (18.6 mi) of roads and five bridges in a critical-access corridor.

Gathering Data

Hurricane Maria also emphasized the need for real-time information to prepare for, manage, and reduce the risks of such natural disasters. Prior to the grant, just two stations in Dominica collected weather data, located at the airports on opposite sides of the island. The creation of the country’s hydrometeorological network provides needed data.

As Hurricane Maria passed over Dominica in September 2017, intense rainfall caused flash flooding and landslides.

As Hurricane Maria passed over Dominica in September 2017, intense rainfall caused flash flooding and landslides.

“Data collection is critical to provide information for all our efforts,” Guiste says. “It informs everything from building requirements to warning systems.”

Dominica measures about 47 km (29 mi) long and 26 km (16 mi) wide,4 with an area of 750 sq km (290 sq mi).1 However, its mountainous topography causes the weather to vary dramatically. Heavy rains high in the mountains fill lakes, reservoirs, and streams until they overflow, but that wasn’t captured by the weather stations on the east and west coastlines.

“To reduce vulnerability, Dominica created a very robust system to capture what is happening,” he explains.

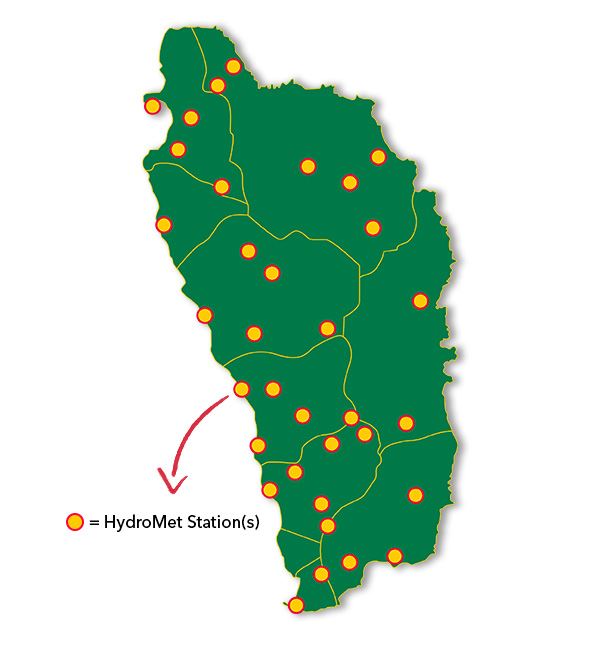

Extensive data from 34 locations in the hydrometeorological network provide real-time information and alerts.

- All locations have strategically placed rain gauges.

- Four stations include weather sensors for air temperature, relative humidity, barometric pressure, and wind speed and direction.

- Nine locations include water level sensors that provide flood monitoring and alerts, placed in mountain-top reservoirs and rivers in the valleys. Future work will allow flow data to be calculated from river water levels.

Dominica's new hydrometeorological network includes 34 systems installed at sites scattered across the country, each providing real-time data to the Dominica Meteorological Service.

Dominica's new hydrometeorological network includes 34 systems installed at sites scattered across the country, each providing real-time data to the Dominica Meteorological Service.

Plus, the World Bank grant supported the establishment of a national geodetic network and embarking the national Light Detecting and Ranging (LiDAR) and bathymetric survey, providing detailed information about the island’s landscape, including the floors of water bodies. Mapping soils across the island identified soil types and chemical properties.

Understanding characteristics like water holding capacity and stability connects rainfall to landslide risk and guides engineering and agricultural investments. Tidal monitoring reveals changes in ocean waters, which can influence flood levels along the coast.

Navigating Terrain

The mountainous rainforests that earned Dominica the nickname “Nature Island of the Caribbean” created unique challenges for putting the network in place. The terrain is not hospitable, even for small weather stations.

A team of experts from multiple government departments and outside consultants surveyed the country to determine data collection points. They identified critical watersheds and anticipated locations most likely to receive rainfall indicative of potential floods or landslides. Many of these points were high in the mountains to capture the heavy rainfalls from clouds trapped there. For recommended locations on private property, landowners and farmers willingly cooperated to host a station and support the effort to protect their families and neighbors.

A team of experts from multiple government departments and outside consultants surveyed the country to determine data collection points. They identified critical watersheds and anticipated locations most likely to receive rainfall indicative of potential floods or landslides. Many of these points were high in the mountains to capture the heavy rainfalls from clouds trapped there. For recommended locations on private property, landowners and farmers willingly cooperated to host a station and support the effort to protect their families and neighbors.

Dominica’s disaster reduction team then worked with Xylem for equipment and installation. Matt Previte, business development for YSI, a Xylem brand, was part of that team.

YSI’s Services team and a local contractor commissioned the stations and provided training to Dominica Meteorological Service staff.

YSI’s Services team and a local contractor commissioned the stations and provided training to Dominica Meteorological Service staff.

“Locating the monitoring stations was a key decision,” he explains. “Scientifically, equipment needed to be in the best place to collect and send accurate data. But, the ability to easily access it for maintenance was also critical, as poorly maintained stations result in poor data quality.”

“The weather stations must operate reliably during severe weather, even up to wind speeds of 150 mph (241.4 kph),” Previte notes.

His team selected specific equipment for each data collection site, accounting for accuracy and durability. YSI Amazon bubblers measure water level in some locations, while others use a noncontact solution, YSI Nile radar sensors. Rain gauges employ a tipping bucket mechanism to empty automatically.

Due to the rugged terrain, and to protect against vandalism, stations required conduit for the wiring to connect rain gauges or other sensors to the data logger and battery. Installers carefully navigated to hard-to-reach spots, like down cliffs and at specific underwater depths.

Dominica is the most mountainous island in the Lesser Antilles, a rugged landscape contributing to the constant threat of flash flooding.

Dominica is the most mountainous island in the Lesser Antilles, a rugged landscape contributing to the constant threat of flash flooding.

YSI’s Services team worked with a local contractor to successfully install the data collection network. They monitored and maintained it together for the first year of operation. This strategic collaboration provided more time for training and learning as the network management transitions fully to the Dominica Meteorological Service.

Maintenance will be an ongoing challenge because of the terrain. Still, project leader Collin Guiste says it will be a critical priority for the Dominican government to make the investment worthwhile.

Solar-charged batteries power each automatic weather station to run sensors and capture data, storing power to continue operating 24/7 and during weather events. Satellite antennas transmit data to a Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellite (GOES), preventing disruption.

Applying Intelligence

The GOES satellite continuously downloads the weather network data to a receiver station at Dominica’s hurricane-proof meteorological office. Xylem also installed servers there to store data and run the World Meteorological Organization’s (WMO) data modeling software. The program automatically analyzes data that is cross-checked for verification by staff. Since the components were fully installed in June 2023, the team has been working to optimize data use.

“We’ve now built the level of monitoring needed to provide near to real-time information to residents during emergencies,” Guiste reports. “For example, we have the capability to send out an alarm when upper river levels are elevated so residents can take precautions for flooding to save lives and property.”

The monitoring network will provide critical flood-related information to authorities and residents during storm events.

The monitoring network will provide critical flood-related information to authorities and residents during storm events.

He says the alarm system capabilities, which also can be used for tropical storms, are now being interfaced. However, the team is still learning more about those abilities with the aim of adjusting alarm triggers for different threats.

The information from the system has better equipped policymakers, as well. Based on water flow data, Guiste says the Ministry of Public Works changed the minimum size for culverts under roads from 900 mm (35.4 in.) to 1200 mm (47.2 in.). Larger culverts channel water better, increasing rainfall capacity and reducing the likelihood of roads washing away.

Data will continue to support resilient infrastructure design, all with the goal that Dominica will be prepared to better recover from natural disasters. Whether that’s isolated heavy rainfalls triggering flooding and mudslides or the next major storm like Hurricane Maria, reducing the island’s vulnerability will help its people—and its natural beauty—thrive.

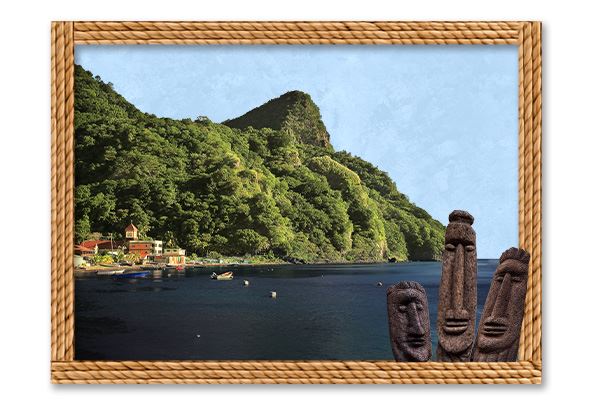

The native Kalinago population is closely connected to the country’s forests. They use indigenous trees to create crafts such as wood sculptures and masks.

The native Kalinago population is closely connected to the country’s forests. They use indigenous trees to create crafts such as wood sculptures and masks.

SOURCES

1 The World Factbook, Dominica

2 The World Bank, Dominica’s Journey to become the World’s First Climate Resilient Country

3 Government of the Commonwealth of Dominica, Post-Disaster Needs Assessment: Hurricane Maria

4 Encyclopedia Britannica, Dominica